American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein shook up the art world with his comic-strip inspired paintings and his bold reproductions of cartoon characters. He took images from popular culture, and reproduced them in his art to create new contexts and meanings, becoming one of the most famous pop artists of all time. Lichtenstein also made sculpture, prints and ceramics, but is best remembered for his painted works.

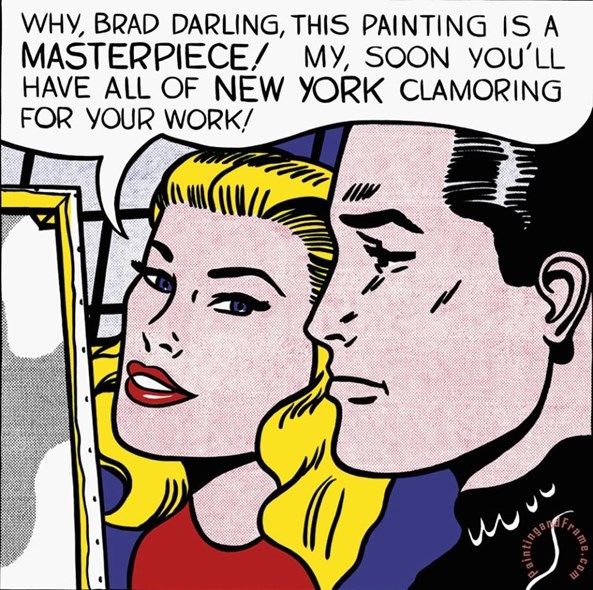

Image: Roy Lichtenstein, Masterpiece, 1962, in 2017 the painting sold for $165 million

American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein shook up the art world with his comic-strip inspired paintings and his bold reproductions of cartoon characters. He took images from popular culture, and reproduced them in his art to create new contexts and meanings, becoming one of the most famous pop artists of all time. Lichtenstein also made sculpture, prints and ceramics, but is best remembered for his painted works.

Roy Lichtenstein, Masterpiece, 1962, in 2017 the painting sold for $165 million

Born in New York city in 1923, Lichtenstein grew up in a city and an era characterised by prohibition, mass commercialisation, advertising and jazz. The American culture was exploding outwards in all directions and mass consumption was shaping the way the nation viewed itself.

Lichtenstein had a keen interest in art and music from an early age. To complement his otherwise entirely academic education, he enrolled himself in classes at the New York School of Fine and Applied Art and later at Ohio State University. In 1943, his studies were interrupted and he was inducted into the military, where he served until the end of the war. During his time in service he visited Paris and London, learning more about European art and style.

After the war Lichtenstein returned to Ohio where he finished his degree and took a teaching position, returning to New York in 1957. Once there, he took a position as Assistant Professor at the State University of New York. He taught industrial design. It was during this period that Lichtenstein is thought to have first used cartoons and comics as inspiration for his work. In 1960 he moved to Douglass College at the State University of New Jersey where he met Allan Kaprow who inspired him to focus on comic books as his source material.

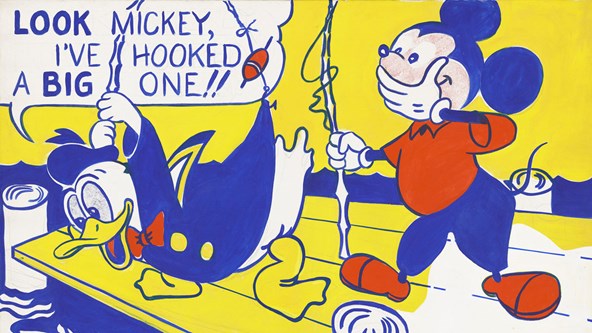

In 1961 Lichtenstein painted Look Mickey, which is widely acknowledged as his first pop art painting, cementing him as a defining artist of the era and rocketing him to widespread recognition. In 1960 he was taken on by the art dealer Leo Castelli. By 1996, Lichtenstein was chosen as one of five artists representing the USA at the Venice Biennale.

Roy Lichtenstein, Look Mickey, 1961

For Lichtenstein’s comic paintings, he often used four basic paint colours that reflected the colours available to newspaper and magazine printers. He often also used dots to colour his paintings, a system known as the Ben Day dot system and used by newspapers to increase the range and effect of the colours available to them.

At the height of his career, Lichtenstein produced several works that were drawn from comic strips. Comics had risen to popularity in the 1950s and were rapidly becoming icons of a fast-paced consumer market and a fairly generic, passive consumer audience. They provided the perfect symbolic reference for Lichtenstein’s pop art perspective.

Lichtenstein would focus in on a particular image or detail from the comics and recreate it in his work with minor adjustments. His works may appear simple at first glance, but are technically demanding. He used drawing, tracing, painting, varied brushstrokes and line drawings. Unlike the original comic strips, which were quickly reproduced and printed, his work is often painstakingly detailed and carefully created.

Some of Lichtenstein’s critics have accused him of doing little more than copying the images he works with. He is known to have defended his work by stating that he makes small, almost unnoticeable changes to the composition as well as to the cropping of the image. Lichtenstein mixed the concept of high art – which hangs on gallery walls and is bid for at auction, with the concept of low art which is discarded and often overlooked as being ‘true’ or ‘real’ art. By replicating so called ‘low art’ in his high art style, he challenged the art industry to ask the question ‘what is art and what is worth our time and attention?’ But several of his contemporaries failed to see the challenge Lichtenstein was making, falling into the trap by dismissing his work as banal or lacking in meaning. In 1964 Life Magazine wrote an article about Lichtenstein in which they asked ‘Is he the worst artist ever?’

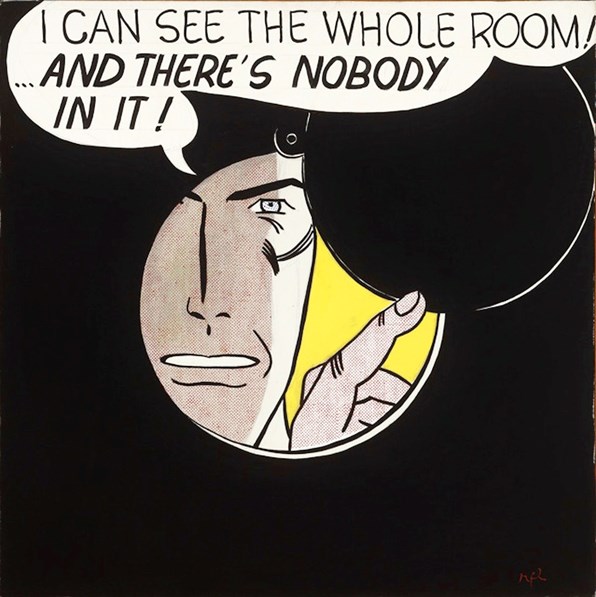

In 2011 his work I Can See the Whole Room and There’s Nobody In It sold at auction for $43.2million. But his work continues to divide opinion.

Roy Lichtenstein, I Can See the Whole Room and There’s Nobody In It

Some people dislike it because it appears ‘detached’ or ‘cold’ – he does not appear to charge his paintings with any emotion or personal experience. On the other hand, others dislike it because it is too accessible – too banal. But within these paradoxes, these criticisms, there seems to be a great and enduring joke being played. Lichtenstein’s work appears simple, but it challenges us in unique, unexpected ways. It defies classification. It is complex in its lack of complexity and entirely unique, although it has been wholesale copied from other sources. We can’t pin it down and it defies our expectations.

The comic book imagery that Lichtenstein played with is the embodiment of dismissible, lowbrow art. It is mass-produced, created for the pleasure of the audience and for commercial gain. By borrowing imagery from it and presenting it to us on the walls of a gallery, created by the hand of a talented artist, Lichtenstein asked the art world to reconsider itself, to ask difficult questions and to move out of its comfort zone.

Roy Lichtenstein, Nurse, 1964, in November 2015, this piece was sold for $95.365.000 at Christie’s New York

In his later career, Lichtenstein moved away from comic strip imagery, although he continued to use the signature Ben Day dot in most of his works. The dots implied reproduction or industrialisation, but as with his comic book works, they set up our expectations of simplicity and mass production only to shatter them. They were hand produced, painstakingly created, one by one.

Lichtenstein died in 1997 after contracting pneumonia at the age of 73.

ArtDependence Magazine is an international magazine covering all spheres of contemporary art, as well as modern and classical art.

ArtDependence features the latest art news, highlighting interviews with today’s most influential artists, galleries, curators, collectors, fair directors and individuals at the axis of the arts.

The magazine also covers series of articles and reviews on critical art events, new publications and other foremost happenings in the art world.

If you would like to submit events or editorial content to ArtDependence Magazine, please feel free to reach the magazine via the contact page.