The British Museum is currently showing the largest collection of the prints of Edvard Munch (1863-1944) to have been exhibited in the UK for 45 years. These include a black-and-white lithograph of The Scream made in 1895, on loan from a private collection in Norway, and a total of 83 prints, sketches and paintings, which together provide a thought-provoking introduction to Munch’s character and Bohemian lifestyle. The exhibition has been organised by Giulia Bartrum, Curator of German and Swiss prints and drawings at the BM, in collaboration with the Munch Museum, Oslo.

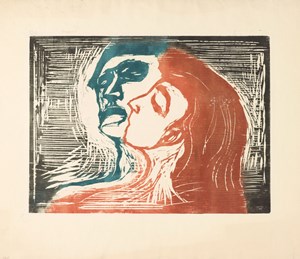

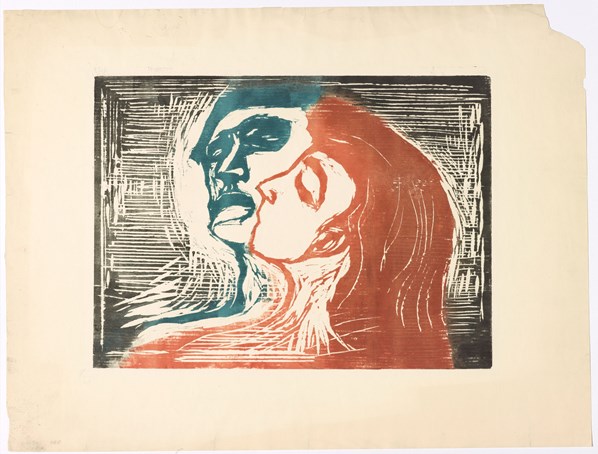

Image: Edvard Munch, Head by Head

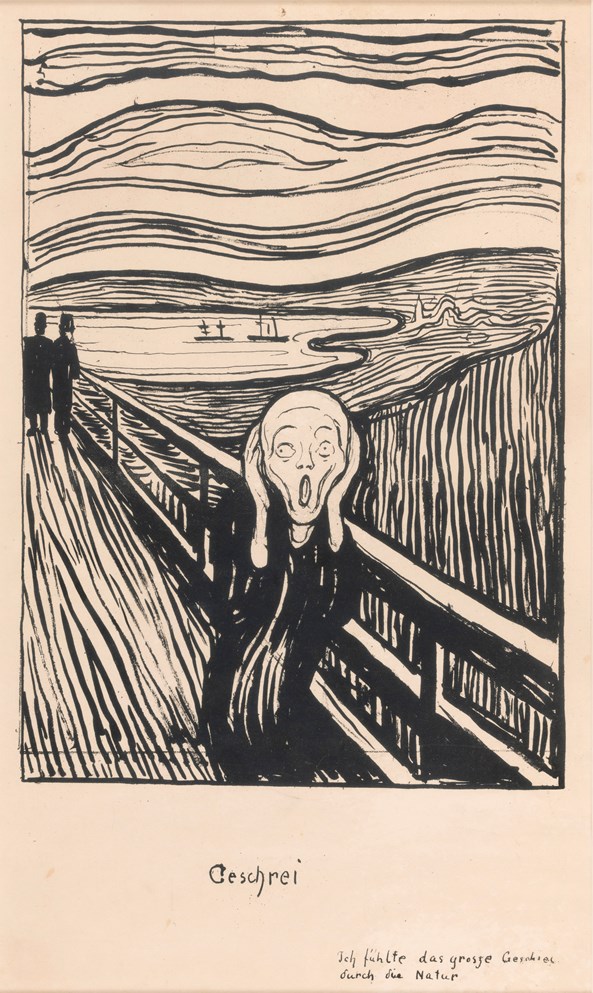

To many people, the name of Edvard Munch is synonymous with The Scream: an image, an icon, even a meme, that embodies the existential angst of the twentieth century.

Beyond The Scream, Munch’s reputation today rests primarily on his symbolic, emotionally charged, and often controversial paintings, and their influence on early twentieth-century movements such as German Expressionism. His importance in the history of graphic art, however, is less well known. Ironically, it was a black-and-white print that first established his international reputation: a lithograph of The Scream, made two years after his first painting of that name, which was picked up by journals in Paris and New York. Following this success, Munch went on to make in the region of 850 print matrices and 30,000 impressions in the course of his prolific career.

Edvard Munch, Head by Head

All the more reason, then, for the British Museum’s latest exhibition in the Great Court Gallery, Edvard Munch: Love and Angst. Its focus is the prints which Munch made between the 1890s and 1918, the period considered his most innovative. While the majority of his prints were based on earlier paintings, he ensured that they did not simply mimic the paintings, but introduced variations in design and colouring.

The exhibition spans seven galleries, organised by theme. They cover Munch’s beginnings in Kristiania (modern Oslo); the highs and lows of erotic passion; the artistic lifestyle in fin de siècle Berlin; his feelings of anxiety and isolation, epitomised by The Scream; illness and death in contemporary society and in his own life; designs for stage sets and posters for productions of Ibsen in Paris; and, finally, his return to Norway, where he lived from 1916 until his death in 1944, on an estate near Oslo. The thematic arrangement alludes to his Frieze of Life, a gradually assembled collection of paintings which he characterised as ‘a poem about life, about love and about death’.

Edvard Munch, The Scream

The exhibition provides an intriguing glimpse into the eccentric characters of the Bohemian circle in which Munch moved in Kristiania, Berlin and Paris. In Kristiania Bohemians II(1895), for example, he depicts himself sitting at a café table with a group of his fellow Norwegian artists and writers. Their pale or shadowy faces stare past each other with sombre pensiveness beneath a coil of cigarette smoke. Munch’s own face is thin, white and apparently pock-marked, like a travesty of a carnival mask. One of the characters depicted is Hans Jaeger, a nihilist who was sentenced to prison for his allegedly blasphemous and immoral book, From the Kristiania Bohemians. There is also a lithograph of him which Munch made in 1896, based loosely on an earlier painting (not displayed). Unlike the painting, the lithograph focuses solely on Jaeger’s head, which gazes out at the viewer from a murky black background, the brim of his hat turned down over his forehead, his face half in shadow. The contrast between the heavy black ink and the off-white paper almost buried beneath it serves to emphasise Jaeger’s cool, rather sinister expression.

A particularly moving print in the ‘Sickness and Death’ section depicts a grieving woman displaying her naked child, who bears the scars of syphilis – the AIDS of the nineteenth century – which he has inherited from his mother. Unusually, the image was derived not from Munch’s personal experience of disease, but from a visit to a hospital in Paris. The painting on which the print is based was judged by the public, he wrote, to be ‘offensively immoral’.

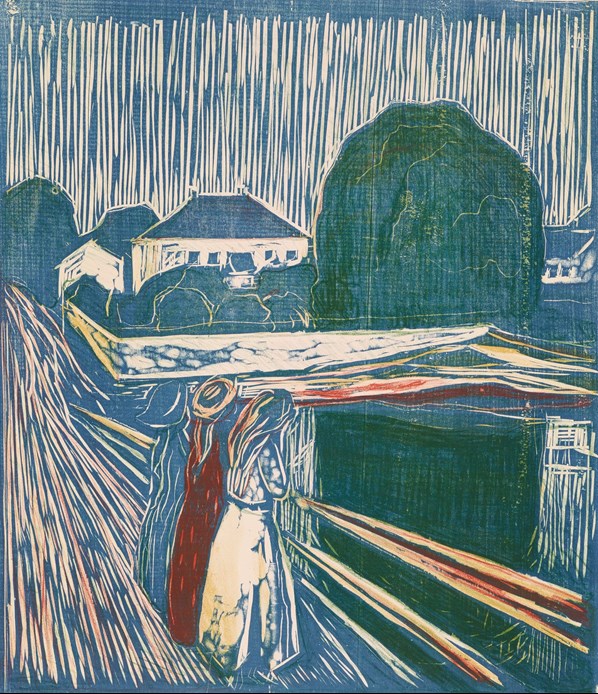

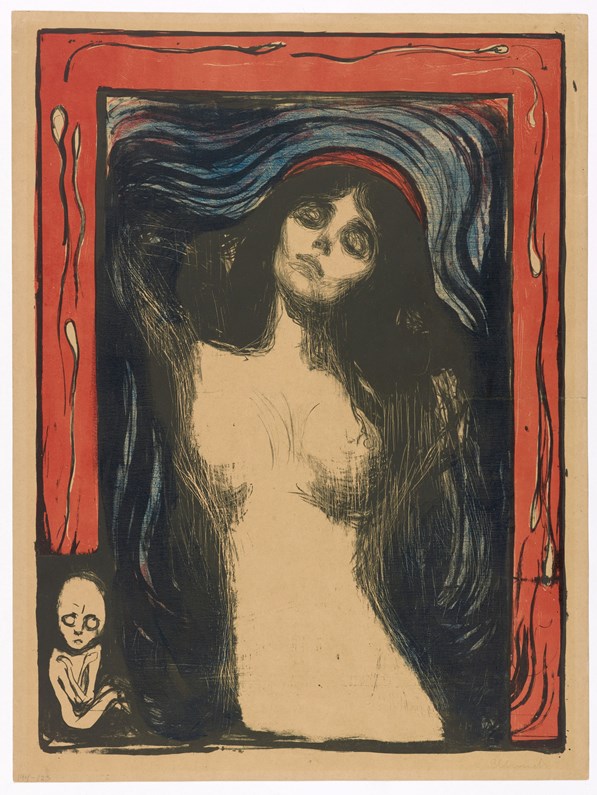

Edvard Munch, Girls on The Bridge

Munch’s depictions of sexual passion and its destructive consequences were frequently too strong for the nineteenth century – in public, at least. This did not stop him, however, from making prints of some of his most controversial paintings. Notable among these is the Madonna, a half-portrait of a naked woman ‘in a state of surrender’, as he put it, her head tipped back and surmounted by a halo. The composition alludes to the depiction of the Virgin Mary by the Old Masters, whom he had closely studied, but transforms their chaste mother of God into a dangerously lascivious woman.

Edvard Munch, Madonna

Munch made several paintings of this image, as well as two print versions, one black and white (1895) and one colour (1902), both of which are on display. In the prints, the woman’s long hair, a motif which he used in other works to symbolise sexual entrapment, flows over the edge of the border suggestively. The border of the prints, but not the paintings as they survive, is decorated with sperm and a goblin-like foetus. This decoration was included on the frame of the first painting, but after its explicitness outraged public sensibility when it was exhibited, the frame was removed and later lost. Fortunately, the prints were spared this fate; this was presumably because prints, unlike paintings, were usually collected and appreciated in private rather than in public.

Comparing the two prints of the Madonna, it is striking how much the colour version, produced seven years after the black and white one, gains from the use of three different tones (black, red and blue). Particularly effective are the blood red of the woman’s halo and of the sperm-lined border, evoking a sense of almost satanic power. The very expressiveness with which Munch used colour is perhaps why, of all the works on display, the black and white lithograph of The Screamis the least striking: the wavy scarlet brushstrokes of the sunset in the original paintings contributes so much to the atmosphere of horror.

It was the sight of this sunset like ‘coagulated blood’, as Munch described it to fellow-painter Christian Skredsvig, that caused him to experience the ‘scream through nature’ which he would later depict not just in The Scream itself but in a number of other works. Some of these are on display in the ‘Angst and Isolation’ gallery, notably Despair (1892), one of Munch’s earliest sketches of the walk to Ekeberg on which The Scream would be based, and lithograph and woodcut versions of Angst(1896), both of which are derived from Evening on Karl Johan Street (1892), a painting of the afternoon promenade in Kristiania. In Despair and both prints of Angst, the only colours used are black (on a white background) for the landscape and figures, and red for the horrifying sunset. The display of these works alongside the lithograph of The Scream helps to explain why its lack of colour feels disappointing. Or it may be that, unlike Munch’s contemporaries, we as a modern audience are too conditioned by the paintings.

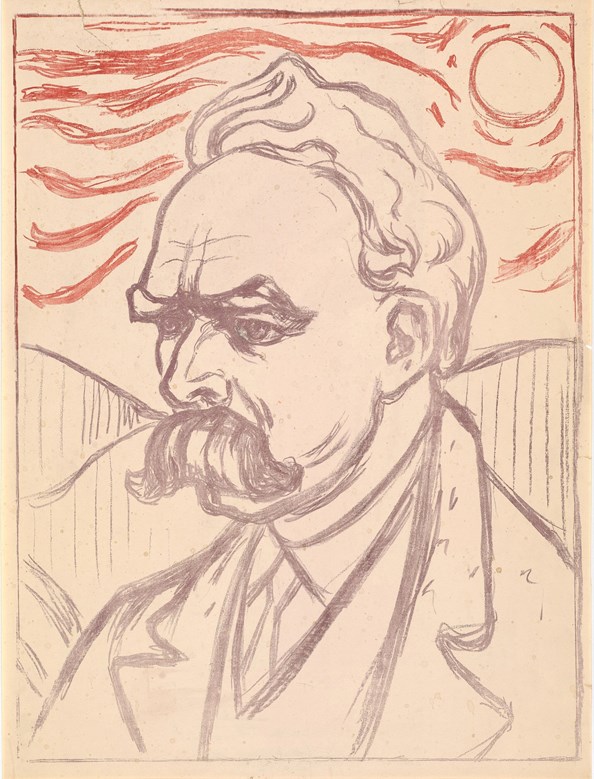

Edvard Munch, Friedrich Nietzsche

Unlike many artists, Munch carefully preserved the matrices of his prints. Three of these are on display for the first time in Britain: the copper plate for the etching of Kristiania Bohemians II; the lithograph stone for Madonna; and the birch woodblock for the woodcut, Head by Head, displayed with two prints, one made in Berlin in 1905 in black ink, and the other made in Kristiania, probably after 1914, in black, red and blue. With their solidity and functional appearance, the matrices evoke the physical labour involved in printmaking, and Munch’s skill, not just as an artist, but as a craftsman. The display of different prints from the same matrix, some executed by Munch himself, some by specialist printers, are a reminder that printmaking was often, unlike painting, a collaborative process –– the final print was the work of the printers as well as of the designer.

This exhibition gives a fascinating insight into the louche friends, lurid imagination, and technical versatilityof a major European artist. Much more than just a Scream.

Edvard Munch: Love and Angst, British Museum, until 21 July, 2019

ArtDependence Magazine is an international magazine covering all spheres of contemporary art, as well as modern and classical art.

ArtDependence features the latest art news, highlighting interviews with today’s most influential artists, galleries, curators, collectors, fair directors and individuals at the axis of the arts.

The magazine also covers series of articles and reviews on critical art events, new publications and other foremost happenings in the art world.

If you would like to submit events or editorial content to ArtDependence Magazine, please feel free to reach the magazine via the contact page.