If you were looking for a stereotypical cultural conservative, you might well choose someone Swiss, or someone with their own haberdashery store, a petit bourgeois like Hermann Rupf. But the fact of the matter was that this unlikely and unwealthy private individual was one of the first to see merit in the work of the cubists, fauve André Derain, and abstract art.

If you were looking for a stereotypical cultural conservative, you might well choose someone Swiss, or someone with their own haberdashery store, a petit bourgeois like Hermann Rupf. But the fact of the matter was that this unlikely and unwealthy private individual was one of the first to see merit in the work of the cubists, fauve André Derain, and abstract art. He bought direct from the studios of some of the 20th century’s greatest emerging artists, at a time when most collectors were drawn to classical art.

Rupf was not only an enterprising small businessperson, he was a militant socialist. He not only sold ladies tights and gloves, he wrote art criticism for a local newspaper. He was not a millionaire, but he used stock buying trips to Paris to add to his collection. Most of the paintings he acquired were small enough to fit under his arm for the long journey back to Bern. It is a domestic collection, but features the wildest visual ideas of the last 100 years.

By the time of his death in 1962 he was the owner of some 70 masterpieces of what was at the time contemporary art. Between 1903 and 1904, a year that was to set the tone for the rest of his life, he shared an apartment in Paris with broker Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. Rupf and his German friend were eager consumers of exhibitions, concerts, plays and art history. When Kahnweiler, who stayed in the city, to open a gallery, Rupf was among the first to give him custom.

André Derain, Paysage aux Environs de Cassis (1907). Image courtesy Rupf Collection.

The fruits of this extraordinary biography can be seen currently at the Guggenheim in Bilbao. The split-fruit outline of Frank Gehry’s landmark building finds an echo in the jumbled planes of some eight cubist works by Braque along with examples of the genre by Gris, Leger, and of course Picasso. It is overwhelming to think of a middle class culture vulture having the foresight to build a collection this wonderful.

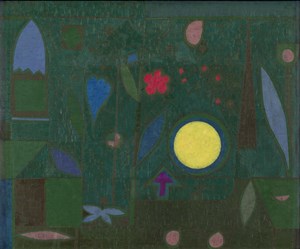

But it would be a mistake to think that anyone could try their hand at this. The 20th century art world was a much smaller place. Pre-war Paris was the very centre of aesthetic innovation and the players were easier to identify, meet and buy from. Rupf and Kahnweiler became friends with their artistic heroes. Paul Klee, for example, was a good friend and six of his pictures are in this show. If you were to look around for a 21st century Klee, a quietly mystical producer of small but well-formed paintings that nevertheless push boundaries, there are surely not even any contenders.

Paul Klee, Vollmond Im Garten (1934). Image courtesy Rupf Collection.

This is the most instructive aspect of the Guggenheim’s show, the rupture between contemporary art we now call modern and the contemporary art we now find in London, Berlin, New York and far beyond. In order to thoroughly get under the skin of our present day visual culture it would not be enough to decamp to Paris for twelve months. One would have to clock up a good many air miles, visiting fairs, Biennials and outposts of the art world, like Bilbao itself.

Activities of the Rupf Foundation since the death of Hermann and Margrit bear out the difficulties of honing a collection in the postmodern era. For a while in the 1980s, they collected from the studios of artists in and around Bern. More lately they’ve been exploring the longevity of minimalism. Half of this show, which features Carlos Bunga along with Kandinksy, reveals a quickly loosening grip on the zeitgeist, an unravelling which leaves us where we are now.

Georges Braque, Violin et Archet (1911). Image courtesy Rupf Collection.

The visitor might reflect, yet again, on the excitement and drama of modern art in the crucible of modernity, and the added excitement of collecting the biggest names in modern art for a relative song.

La Colección de Hermann y Margrit Rupf can be seen at Guggenheim Bilbao until April 23 2017.

ArtDependence Magazine is an international magazine covering all spheres of contemporary art, as well as modern and classical art.

ArtDependence features the latest art news, highlighting interviews with today’s most influential artists, galleries, curators, collectors, fair directors and individuals at the axis of the arts.

The magazine also covers series of articles and reviews on critical art events, new publications and other foremost happenings in the art world.

If you would like to submit events or editorial content to ArtDependence Magazine, please feel free to reach the magazine via the contact page.