In an era where intimacy has become a new technology, Gupta counters such franchised interests, by contextualising the lives of the individual, as they manage less to strive but to survive the altering condition of modernity.

Jointly representing India and Pakistan for the 56th Venice Biennale (2015), with Lahore based artist Rashid Rana, Shilpa Gupta might well appear to be acting out one of her artworks, by seeking the ultimate elasticity between borders. Dissolving boundaries between countries, Gupta’s mutual pavilion participation is explained by Rashid Rana, as being about the “freedom of movement and ideas.” And for Gupta this kind of pluralistic rhetoric explains much of her intention for art to be part of a more populist movement in the region. Enabled and envisioned by an artist acting as facilitator, for an audience who are rightly able to engage with her works very directly. And in contexts that are closer to the routine of reality. Much of the performative element of Gupta’s work are conducted more evanescently. By which she replaces the laboratory styled gallery space with situations and sites that expound street life. Gupta is known for infiltrating unsuspecting audiences in market places and on third class train carriages, in an attempt to feel the pulse of ordinary people. As she is convinced such arbitrary points of contact lead to greater reactions to her artworks. And it is the impossible measure of people of all walks of life coming into contact with one another that allows Gupta the liberty to impress upon them works that address notions of identity politics, and of the geography that defines us all.

Intensely perspicacious, Gupta has amassed an impressive cannon of international exhibitions that demonstrate her ability to transmit her creative energy to as big an audience as possible. And as an artist she uses the circumstances of those who are having to exist on the periphery, as the source material for much of her work. Between physical boarders in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, and the more personal boundaries of social infringement and inequality. In an over populated country fashioned entirely by religion, and the crippling bureaucracy of institutions and organisations, Gupta appears to want to challenge our perception of what is reasonable, within the macro and micro infrastructures of the lives of ordinary people. With artworks that are less aesthetically pleasing. But more work-man-like survey pieces, which prove more critically engaging. Yet crucially as much as she might be averse to existing social structures; Gupta antipathetic approach demonstrates something much more valuable. Which is of a country that allows for the kind of debate that Gupta is wanting to cultivate.

As though drawing a line in the sand, Gupta’s connects criticism with a heightened level of engagement. And defines herself as someone striving for a greater liberalism of the arts, for her version of art on the move. In which the causal effect of engaging more directly with her audiences, becomes the platform from which new ideas as artworks come about. For Gupta this is art as information; art as the transferal of energy; art as the empowerment of the many, by an army of one. “I have always wondered if it might have been possible for there to be no label for ‘art’, and if ‘art’ could have been more integrated into our daily life.” Explaining “While I have to use the word ‘artist’ as it is the easiest clue as to explain ones practice, to a patient listener I would say that I work between art and life, which in-turn is connected with the medium and method. I am interested in ‘definitions’ and often use the wide range of material that is available around this to explain myself.”

And Gupta has engendered a practice that permissions her the privilege to unearth a whole set of alternatives ways of thinking.

In an era where intimacy has become a new technology, Gupta counters such franchised interests, by contextualising the lives of the individual, as they manage less to strive but to survive the altering condition of modernity.

Interview

Rajesh Punj: Can you begin by initially explaining your practice and approach to making work?

Shilpa Gupta: I have always wondered if it might have been possible for there to be no label for ‘art’, and if ‘art’ could have been more integrated into our daily life. In fact in ancient Japan, names were always considered taboo, as they feared it would bring ill-luck. While I have to use the word ‘artist’ as it is the easiest clue as to explain ones practice, to a patient listener I would say that I work between art and life, which in turn is connected with the medium and method. I am interested in ‘definitions’ and often use the wide range of material that is available around this to explain myself.

Shilpa Gupta, 100 Hand drawn Maps of India, 2007 - 2008, courtesy: Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, India and Shilpa Gupta

RP: Can you talk more specifically about your current group show, Don’t You Know Who I Am? (13 June – 14 September 2014), at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp, and of the works you have there?

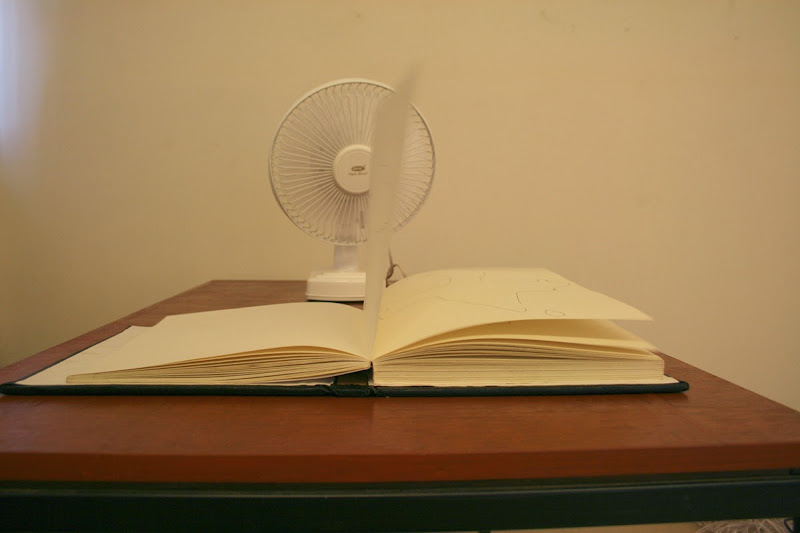

SG: The exhibition at M HKA in Antwerp is a large group show in which I have three works on display. Two are part of a project called While I Sleep which consists of Singing Cloud 2008- 2009, and Untitled (Motion Flapboard) 2012. Both look at movement, geography and perception. Another work, Someone Else - A library of 100 books, written anonymously or under pseudonyms 2011, can also be said to look at movement more from the perspective of feeling free to write where authors have taken on false names or written anonymously to escape the burden of a given name.

RP: Of your contribution to the Edinburgh Art Festival, for the WheredoIEndandYouBegin group show at the City Art Centre; (the title of the show taken from your 2010 neon work installed at the Old Royal High School) what should we make of that work in light of the politics of the Commonwealth, which supposedly unpins the entire show?

SG: Like the text, the meaning is not meant to be conclusive and it works at different levels, concerning continuity between time and groups of peoples. Or it could be two individuals, be it a parent-child and the child who becomes a parent one day, leading to role reversal, or possibly even when the parent ages and becomes childlike. Or it could read against relationships between lovers or even neighbours across a wall, but below the same sky. Even when scrutinising alternative relationships, they cannot become entirely triggered without other relationships having already existed. In the case of Edinburgh Art Festival, the curators selected this existing work and placed in a particular context and location which would be read against the context of the Commonwealth, or the Scottish referendum or even two lovers walking by.

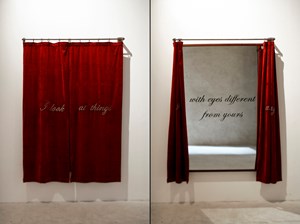

Shilpa Gupta, I look at Things with Eyes Different from Yours, 2010, courtesy: Galleria Continua and Shilpa Gupta

RP: You also have this wonderful site specific work of thousands of microphones and multiple channel audio; I Keep Falling at You 2010, as part of the From Speaker to Receiver exhibition at the Des Moines Art Center in Iowa. Can you explain the piece; which visually appears incredibly arresting?

SG: This is a large amoebic shaped form suspended from the ceiling; the skin of which is made out of thousands of small microphones. It seems perhaps like a disembodied creature as if in a state of sunken stillness. In an unusual occurrence, in a moment of hysteria there has been a reversal, and the microphones growing on its skin, have begun to whisper and to sing by themselves in the absence of a listener. The multitude of voices, rise and sink in a call for a shift.

I keep falling at you

But I keep falling at you (chorus, repeat)

Your garden is growing on me

I will take it away with me

To a land which you can mark no more

Where distances don’t grow anymore

I keep falling at you

But I keep falling at you (chorus, repeat)

RP: And then you also have a work at the Faurschou Foundation, Copenhagen. For the I Look at Things... exhibition. Which is taken from the title of your work I look at Things with Eyes Different from Yours 2010. What should we make of that?

SG: The mirror work is about perception and limitation of looking and knowing. There are multiple ways to read the work and it can be mapped for the internal self or a larger entity; group, text, object. On the one hand it is about the limitation of the self. Where physiologists claim that a rather large part of the human action, operates not via our consciousness but our unconsciousness. Suggesting that we ourselves may not be fully aware of our actions. On another level the work questions strict definitions, as ideas become history which is always prone to be re-written and re-imagined. The work is about multiplicity in that sense.

Shilpa Gupta, Untitled (Motion Flapboard), 2012, courtesy: Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, India and Shilpa Gupta, photo credit Anil Rane

RP: The show also has works by the late American artist Robert Rauschenberg; the Iranian American film-maker Shirin Neshat; and the Chinese artists Zeng Fanzhi, Zhang Huan and Cai Guo-Qiang. Are you ‘Indian’ by default, when you are in a show of international artists defined as much by their art as their geography, and how do you negotiate that?

SG: To this I would request the viewer to look at the work minus the name of the artist and make a guess as to where the artist is from.

RP: Prior to that you have just had the work Untitled 2013 - 2014, at the 8th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, curated by Juan A. gaitán. In which you have a text piece engraved onto concrete, or etched into grey coloured stone; with a line that resembles a slash, accompanied by a paragraph of political rhetoric from the era of partition in India. What are you wanting of your audience when they look at this work?

SG: The work is not about partition. The stone is shown along with several different works.

RP: I am also interested in your explaining your work for the LANDSEASKY, revisiting spatiality in video exhibition, curated by Kim Machan, at the OCT Contemporary Art Terminal, Shanghai; in which you had shown 100 Hand drawn Maps of India 2007 - 2008. Is that a work that is part of an on-going series dealing with territory?

SG: In 100 hand-drawn maps of India, a hundred people are asked to draw the map of their country by memory. None of the lines match. Some even include Sri Lanka unconsciously. The work is about the complex relationship between a large entity like a state and an individual.

Yes it has since grown into an ongoing series where I have collected maps from Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, and different parts of Italy, Cuenca, etc. And currently I have a book of 100 pages is circulating in Edinburgh.

Shilpa Gupta, Someone Else - A library of 100 books, written anonymously or under pseudonyms, 2011, courtesy: Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, India and Shilpa Gupta, photo credit Anil Rane

RP: How political are you wanting to be perceived? And what are the origins of your activism?

SG: The word political is overused. I prefer to allow the viewer to simply look at the work. I would be more comfortable if you labelled my work ‘everyday art’, as it comes out of daily living where one grew up in a community where women are asked to not enter temples while menstruating, or of growing up in a neighbourhood by the sea; which is very hybrid. Or alternatively traveling to the edges of a country, where upon you begin to see the centre and city in a different way.

RP: Your works appear as much determined by words and phrases, as they are by your decision to create an installation of microphones, or project drawings onto a screen. Do you initially coin a phrase or slogan for a work, and then decide upon how to transmit it?

SG: There is no one fixed way of working with form or content. It can be either, or; but a work feels complete when several elements begin to make sense. Form, text and something else. The later is more important than anything else.

RP: Or are you far less of an activist than your work would have us believe?

SG: I suppose by now you would have guessed that I am not comfortable with strict labels and work from an in-between place, where there is a greater possibility of dialogue.

Shilpa Gupta, Singing Cloud, 2008- 2009, Commissioned by Le Laboratoire, Paris, courtesy: Arnolfini, Bristol, UK and Shilpa Gupta

RP: As a young woman artist preoccupied with politics, and of the fall-out from the rise of modern India; how are you received by audiences in India?

SG: While there has been great support, I also know my work makes certain people uncomfortable. Which is rather unnecessary, as I feel there is a place for several voices and different kinds of practices to exist at the same time.

RP: And having exhibited extensively now, do you consider your work transmits better to a western audience than to those who attend your shows in India?

SG: This is a question based on someone reading the list of shows that my works have travelled to and considering them more international. I have actually shown a lot in Japan and Korea and Australia too, so would these be considered Western too?

I have had equally intense feedback from people irrespective of location. From my experience nation state geography is hardly a way to create definitions. When I showed There is No Border 2005-2006, which came out my experience in Kashmir at the Havana Biennale. I had a reaction which was more intense than in New York or even Mumbai. So does that make me an artist from Cuba? Then there are times, I have shown my work on the streets in my neighbourhood or in a local train, and have received reactions have been incredibly moving.

Shilpa Gupta, WheredoIEndandYouBegin 2010, courtesy: Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, India and Shilpa Gupta, photo credit Czetan Patil

RP: Phrases such as ‘post-colonialism’, ‘generational conflicts’, ‘globalisation’, ‘diversity’ and ‘differences’, are used to describe your work. Are you intent on taking on such complex and colossal ideas as art?

SG: These are all terms used to understand the present. It is true that some people feel that these words are not necessary, which is also fine.

RP: With your 2002-2004 work Blame, were to trying to rationalise issues about identity politics? And how was the work received by an audience?

SG: I would take a local train, get into the women’s compartment, carrying a box of Blame bottles, open it and as they would sometimes leak, start to clean them. Women around me, start to ask me what it was and soon the 20-30 bottles would disappear from the box and get passed around. The reactions ranged from a level of discomfort, and conversations; to a woman buying a bottle to take for her son, to another woman giving me a thumbs up at a distance getting off the train. I was amazed at the reaction of people. From an art gallery and non-art gallery audience alike, and even last week I met a lawyer who had picked up the Blame bottle 10 years ago somewhere, and she said this was one of her favourite works. We even managed to perform the Blame project in Perth with a bigger group of volunteers with Blame T-shirts and distributed several Blame bottles in different places. Starting from the street outside the art gallery to the public square around it, and in the little lanes in the city centre. In shopping malls, and we also joined a suburban Sunday market. The reactions were varied and ranged from those who would wished not to participate, to intense conversations. And even aggressive behaviour. I also remember someone returning back to take a bottle for a friend.

Shilpa Gupta, There is No Border, 2005-2006, courtesy: Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, India and Shilpa Gupta

RP: Untitled (There is no Border Here) 2005-2006, (shown at the La Cabaña Fortress, Havana Biennale), has a flag text in adhesive tape applied to the wall. An incredibly poetic text of the uncertainty and abstraction of deciding upon terrorises, as you might try and take control of the skies. Are these your own words?

SG: Yes they are my own words.

Berlin Biennale für zeitgenössische Kunst / 8th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art (29.5.2014–3.8.2014). Selected works commissioned by the Samdani Art Foundation for the Dhaka Art Summit 2014 with additional support from Majlis.

Shilpa Gupta, Untitled, 2013–14, Installation view, courtesy: Shilpa Gupta, Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, photo: Anders Sune Berg

Shilpa Gupta, Untitled, 2013–14, Installation view, courtesy: Shilpa Gupta, Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, photo: Anders Sune Berg

Shilpa Gupta, Untitled, 2013–14, Installation view, courtesy: Shilpa Gupta, Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, photo: Anders Sune Berg

Shilpa Gupta, Untitled, 2013–14, Installation view, courtesy: Shilpa Gupta, Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, photo: Anders Sune Berg

Rajesh Punj, August 2014

ArtDependence Magazine is an international magazine covering all spheres of contemporary art, as well as modern and classical art.

ArtDependence features the latest art news, highlighting interviews with today’s most influential artists, galleries, curators, collectors, fair directors and individuals at the axis of the arts.

The magazine also covers series of articles and reviews on critical art events, new publications and other foremost happenings in the art world.

If you would like to submit events or editorial content to ArtDependence Magazine, please feel free to reach the magazine via the contact page.