Beyond the canvas posters of Swiss-French designer and architect Le Corbusier, the Pompidou’s idiosyncratic building in central Paris also plays host to a retrospective styled exhibition of Beirut born, London and Berlin based artist Mona Hatoum. Whose work has since the early 1980’s been concerned with the trappings of control; as it proved the invasive ingredient for her Palestinian up-bringing. Leaving Lebanon for London in 1975 as a consequence of civil war, Hatoum’s work draws attention to the lives and landscapes of those permanently under seize and out of place.

Beyond the canvas posters of Swiss-French designer and architect Le Corbusier, the Pompidou’s idiosyncratic building in central Paris also plays host to a retrospective styled exhibition of Beirut born, London and Berlin based artist Mona Hatoum. Whose work has since the early 1980’s been concerned with the trappings of control; as it proved the invasive ingredient for her Palestinian up-bringing. Leaving Lebanon for London in 1975 as a consequence of civil war, Hatoum’s work draws attention to the lives and landscapes of those permanently under seize and out of place. As she is tormented as much by geography, as it is delineated by territorial maps and unsolved peace accords; as she is the intrusion of external and internal forces upon her own body. And as a consequence the exhibition Mona Hatoum reads like a chilling curiosity shop of objects and installations that are as tender as they appear traumatic.

Originally adopting video and performance as a subversive device for which she would take centre stage; the artist moved in the nineties toward more problematic installations and sculptural works that gave scale to her edgy ideas. As Hatoum profited as much from her preoccupation with prefabricated materials, as she did with those made from a more personal touch. And in situ neon, glass, wrought iron and metal, are propositioned as the equals of reams of the artists own hair, nails and urine.

And with more than one hundreds works thematically and not unchronologically on display, the Pompidou’s characteristic glass fronted facade provides an impressive, if not slightly incohesive open plan setting for the uneasy works of an artist who returns to the same symbols, as though they are a nuisance that need to be put-to-bed. And beyond the initial interference of Hatoum’s repetitive video work that hangs as an unsophisticated billboard, lies the visual strength of major works such as Present Tense 1996/2011; that as a motif is central to the artist’s life and lexicography. Reluctant to engage more directly with politics, when interviewed for the Tate Hatoum explained that it can in certain situations be the work’s elixir. “Sometimes the situation I am working in can be politically charged; for instance in 1996 I was doing an exhibition in Jerusalem, and I came across this map of the Oslo peace agreement, which was drawn between Israel and the Palestinians, so I decided to draw this map on a bed of soap. Maybe instinctively I did it on soap because by implication it is a temporary material and eventually it will dissolve, and with it all these boarders will disappear.”

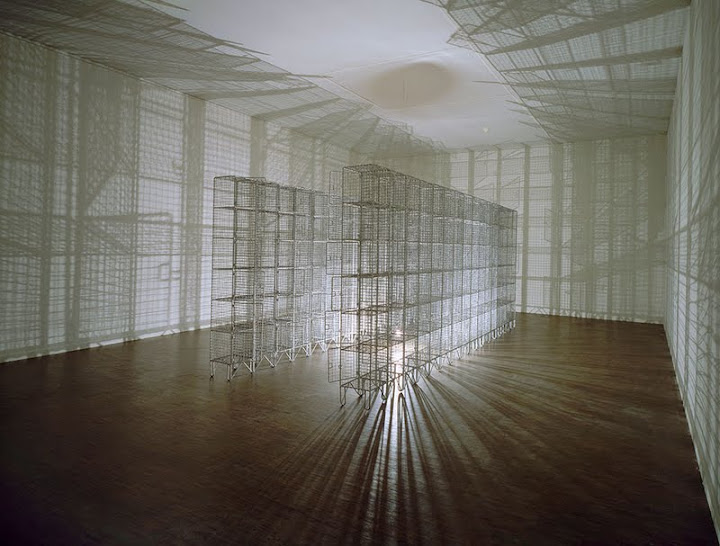

Light Sentence, 1992. 36 wire mesh compartments, electric motor, light bulb 1.98 x 1.85 x 4.90 m © Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris. AM 2009-56 © Photo : Centre Pompidou, Mnam-CCI / Dist RMN-GP [Philippe Migeat]

Light Sentence 1992, proves another seminal work for which Hatoum plays with a sliver of light as a disagreeable condition of solitary confinement. Encompassing a thread of wire and a reticent light-bulb that rises and falls from within a mesh cage, as a shadow hangs over the work like a potential menace. Less machine sculpture and more infected cell, Socle du Monde (Base of the World) 1992 - 1993, pays homage to Italian sculptor Piero Manzoni, and appears as a purulent magnetic cube covered entirely by dark iron-filings. That upon closer inspection resembles the intricate honeycomb patterns of a bees nest.

More delicate still are Hatoum’s sculptural works that are manufactured as these clinical objects; that have distressingly had all of their comforting characteristics removed. As though humanity has lost its heart as a consequence of a history of violence. And Hatoum recalls how these more intimate works resonate a greater disquiet. “Often the work is about conflict or contradiction, and often that conflict or contradiction can be found within the object. A work like Untitled (wheelchair) 1998, on the one hand the person using the wheelchair would need someone to wheel them around, but the presence of the knives, makes you realise they resent that dependence. And as a consequence there is a whole internal conflict happening with that piece. And the work Incommunicado 1993, has these bars that are there for protection normally. But when you approach it you realise the platform has been removed, and instead you have these very taut wires. So immediately your perception of the object changes. It is not anymore about protection, but it is more about a situation of abuse or danger.”

Cellules, 2012-2013. Mild steel and blown glass in 8 parts. 170 cm x variable depth and width © Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris © Photo : Florian Kleinefenn

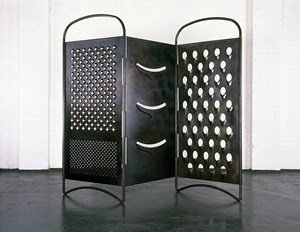

Grater Divide, 2002. Mild steel. 204 x 3.5 cm x variable width Artist’s proof © Courtesy of the artist © Photo Courtesy White Cube [photo Iain Dickens]

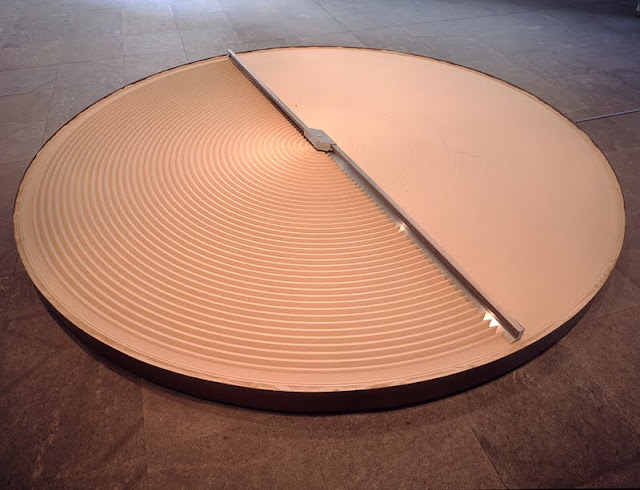

+ and -, 1994-2004. Stainless steel, aluminium, sand, electric motor. Height: 27 cm, diameter: 400 cm © Hall Collection © Photo Courtesy Mataf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, [photo by Markus Elblaus]

Nominated for the Turner Prize in 1995, Hatoum turned her attention from works addressing social and political unease, to the deceptive neutrality of domestic objects that out of context, appear as these misshapen tools of torture. Quarters 1996, is a work made-up of a series of metal bunk beds that rise from floor to ceiling as five skeletal bed frames that for their industrial simplicity recall animal pens, as much as they resemble the most basic space available for sleep. A work’s whose corrosive silence is punctured by the abrasive sounds that resonate from Hatoum’s 1999 installation Home; in which a table of forensic styled kitchen utensils appear to have been wired up to a live electric current and lights. All of which generates a series of temporary aftershocks for an audience standing behind a wire fence, as though voyeurs to the electrocution of domestic and daily bliss, or of life itself. ‘Home’ like ‘Light Sentence’ has an underlying edge that conditions much of Hatoum’s work, with a contradictory juxtaposition of positive and negative influences. And the work also recalls a second installation from the series, entitled Homebound 2000, which comprises of a misplaced junk-shop of charmless furnishings. That by the artist’s intervention become more harmful instruments of torment and torture. Chairs, tables and domestic objects are tangled up, as though ready to detonate from any kind of human contact.

Hot Spot, 2013. Stainless steel, neon tube. 234 x 223 x 223 cm. Exhibition copy © Courtesy of the artist © Photo Courtesy The artist and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris [photo Jörg von Bruchhausen]

The obvious association of neon lights and wiring to conflict zones is demonstrated in another of Hatoum’s major light works, Hot Spot 2014, in which a sizable neon globe sits on its axis and expels an electrical charge into the atmosphere; that at the same time illuminates bright red. A work in which the neutrality of the world map is replaced by the more unmanageable reality of social and civil unrest. ‘Hot Spot’ suggests that rather than there being country specific wars that the world in its entirety is subject to a more uncompromising climate of unrest and revolution. That has the planet glowing not as a measure of productivity, but by the illegitimate energy of conflict. Leading from the luminosity of one work, to the much darker tender impending tragedy of Impenetrable 2009. A work that hangs from the Pompidou’s exposed ceiling as an immaculate barbed-wire sculpture. And as with all of the artist’s contradictory works appears as visually inviting as it is riddled by more sinister virulence.

Impenetrable, 2009. Barbed wire, fishing wire. 300 x 300 x 300 cm. Exhibition copy © Courtesy of the artist © Photo Courtesy Mataf: Arab Museum of Modern Art [photo by Markus Elblaus]

Of Hatoum’s first major solo show in London in 2000, the Palestinian-American intellectual Edward Said wrote of her work, "No one has put the Palestinian experience in visual terms so austerely and yet so playfully." As accolades go such an endorsement might well have impressed others, but for the artist such direct associations to her identity and the politics that proliferate around her work, prove somewhat problematic. As much of the strength of Hatoum’s practice lies in her ability to comprehend the violation of one’s liberty, from a wider humanitarian perspective. When interviewed by Laura Barnett in 2010 for the Guardian newspaper, Hatoum explains the indivisible link between her work and the politics that is imbued in everything from a kitchen colander to prayer mat. "There is definitely a political awareness that filters through my work, but I'm always trying to do it through the form of the work, not as a political agenda. I don't like it when people hear, 'Oh, she's Palestinian,' and think this must be what the work means. It's a reductive, myopic way of looking." For Hatoum geography is less a specific, and more a position from which to scrutinise the rest of the world.

With Hatoum’s sculptural work’s negotiating anatomical space as though a series of disconnected laboratory experiments, the artist’s perspective alters again with Map (clear) 2014. Which recalls one of her signature motifs, of a map of the world enfranchised to the floor as a fractured layer of hundreds of glass marbles that have been painstakingly composed as a visual template of all of the continents together. Reflecting off of the Pompidou’s impressive panoramic view of Paris, Map 2014, is based on the ‘Gall-Peters’ projection, explained by Hatoum as a more egalitarian representation of the world’s land mass. As the work spreads out as an attractive spillage of individual atoms that collectively impresses upon an audience the motif as a kind of precarious magic carpet.

Waiting is Forbidden, 2006-2008 Enamel on steel. 30 x 40 cm. Exhibition copy 1/2 © Courtesy of the artist © Photo Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris

T42 (gold), 1999. Fine stoneware with gold border, in 2 parts 5.5 x 24.5 x 14 cm. Exhibition copy © Courtesy of the artist © Photo Courtesy White Cube [photo Bill Orcutt]

In light of such decisive works and as an alternative approach to her practice, when interviewed more recently for India’s Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Hatoum talks of the responsive energy that shapes many of her ideas. “In many ways a work happens by itself, and I feel like works can make themselves, and of a feeling of things becoming much more fluid, more intuitive, and impulsive; is something that really works for me. And by just interacting with people. And sometimes a conversation I overhear inspires me to do something.” Which is more evident in some of the artist’s early performative works. Including Don’t Smile, You’re on Camera 1980, for which Hatoum has a series of drawings and hand-written descriptions exhibited along-side a fading black-and-white video work of an unassuming audience seated in front of the artist, as she crudely records live footage of their individual body parts; arms, legs, groins; and then superimposes archival material of figures in varying degrees of undress over them; in a mischievous act of identity politics. By way of attempting to challenge social structures. As part of a series of unsolicited performances, that at the time demonstrated variable levels of power upon an unsuspecting audience, society, and country.

Drawing on the gravity of her work, Hatoum pays attention to the endless possibilities for what is to come as a humanitarian and artist, “I think the most exciting thing about being an artist is that I never known where the next exhibition is going to take me to in the world, and what you will end up making. And I find it very exciting, not knowing”; and of the sensation of comprehending reality through the apparatus of art.

Mona Hatoum

Centre Pompidou, Paris, 24 June – 28 September 2015

Rajesh Punj, July 2015

ArtDependence Magazine is an international magazine covering all spheres of contemporary art, as well as modern and classical art.

ArtDependence features the latest art news, highlighting interviews with today’s most influential artists, galleries, curators, collectors, fair directors and individuals at the axis of the arts.

The magazine also covers series of articles and reviews on critical art events, new publications and other foremost happenings in the art world.

If you would like to submit events or editorial content to ArtDependence Magazine, please feel free to reach the magazine via the contact page.